Early educators who engaged in the compensation movement in the 1970s and through the 1990s were not the first to decry the low wages and poor working conditions in early care and education (ECE). They were, however, the first to intentionally mobilize, organize, and lead a movement for change. Whether they called themselves child care teachers or day care workers, family day care or home-based child care providers, caregivers or early childhood professionals, they united under the banner of “Rights, Raises, and Respect.” Inspired by the civil rights and women’s rights movements of the 1960s and early 70s, they were grounded in a belief that change was both possible and imperative.

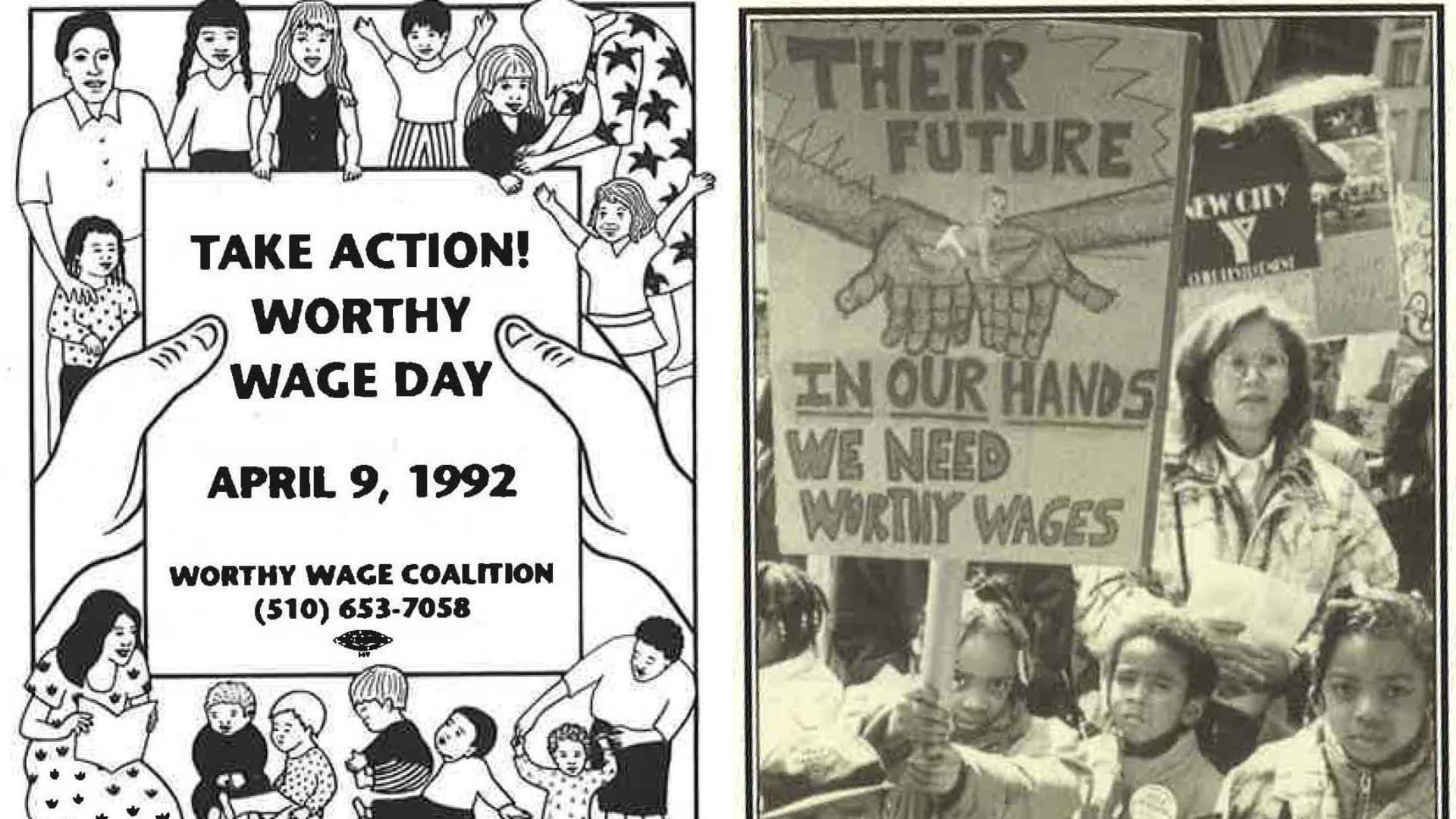

What started as small groups of teachers building relationships with one another in their own communities became larger groups, then networks of groups within and across the United States, and ultimately, the national Worthy Wage Campaign of the 1990s. For the better part of three decades, those engaged in the movement routinely confronted challenges to their organizing efforts. They worked in an industry that was not amenable to unionization, they had to learn a lot to become effective organizers, and they were generally not invited to decision-making tables. These activist teachers approached the many challenges with creativity and commitment to their cause, even as policymakers and ECE leaders not only failed to adequately address their needs, but were generally hostile to the movement.

These activist teachers approached the many challenges with creativity and commitment to their cause, even as policymakers and ECE leaders not only failed to adequately address their needs, but were generally hostile to the movement.

They built an organizational home in the Child Care Employee Project (CCEP), which eventually became known as the Center for the Child Care Workforce (CCW). Through these organizations, educators confronted prominent ECE leaders, developed and shared resources and learning tools, gained media attention, and made their way to policy tables to have their say. They united around strategies aimed at organizing for better pay and working conditions, building collective power, elevating teacher leadership, and engaging in policy and research.

Yet, the struggle for just compensation continues. The Worthy Wage Campaign did not succeed in raising wages to reflect the value of ECE work. It did, however, triumph in other ways. Most importantly, teachers who were initially considered “the radical fringe” and “unprofessional” for talking about raising wages changed the public discourse. The campaign cry, “Parents can’t afford to pay; Teachers can’t afford to stay,” still rings true. Today, this slogan is reflected in public policies across all levels of government with the aim of expanding access and affordability for families, while simultaneously increasing compensation of the workforce.

The campaign also succeeded in changing the way teachers thought about themselves. Emboldened by a firm belief that change would happen as people understood their circumstances, ECE teachers and providers spoke out as never before. Telling their stories might not have been enough to secure the public investment needed to ensure worthy wages, but it was enough to empower teachers to start making changes in their own places of work and to influence policymakers (for example, whistle blowing legislation, salary supplements, and the establishment of scholarship and mentor teacher programs). Together, they defined a good work environment, creating tools for center-based teachers and family child care providers that are still relevant today. Many dedicated teachers remained in their jobs because they recognized that they were in this struggle “for the long haul.” The Worthy Wagers and their actions can inform teacher activism today and inspire the next wave of a teacher-led movement.

Read more: Who Were the Worthy Wagers?